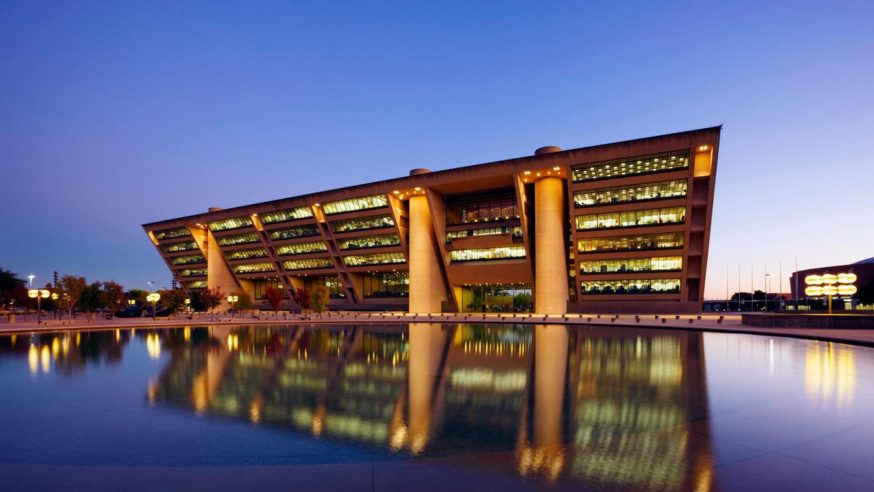

Mayor Pro Tem Tennell Atkins Allegedly Leads Charge to Bar Ex-Felons from City Council Race

Dallas City Council races face a ballot access battle. Are past convictions barring candidates unfairly? A legal gray area

In Dallas, the race for City Council isn’t just about votes; it’s about who even gets a chance to run. A battle over ballot access is exposing a legal gray area while raising questions about second chances and political maneuvering.

Landers Isom III’s campaign for city council was approved on February 7, just three days before the decision would be reversed without explanation.

“My reasons for running are four in part,” Isom explained. “Culture, education, economics, and politics. Our past practices in these areas have us where we are today.” Isom, a program specialist for the City of Dallas and a community activist, sought to represent District 4, a tapestry woven from East Oak Cliff, Cedar Crest, the Lancaster Corridor, and The Bottom. He envisioned a future where “the neglectful and total disregard for the future lives of the children in low-income areas” was replaced with opportunity.

On February 10, a letter arrived, bearing the stark message of ineligibility, slamming the door on his aspirations just after it had been opened. Unbeknownst to Isom, this allegedly occurred off the backdrifts of waves made as part of a larger effort to bar ex-felons from the race entirely. And some report that motivations behind the move were politically-oriented to maintain a status quo.

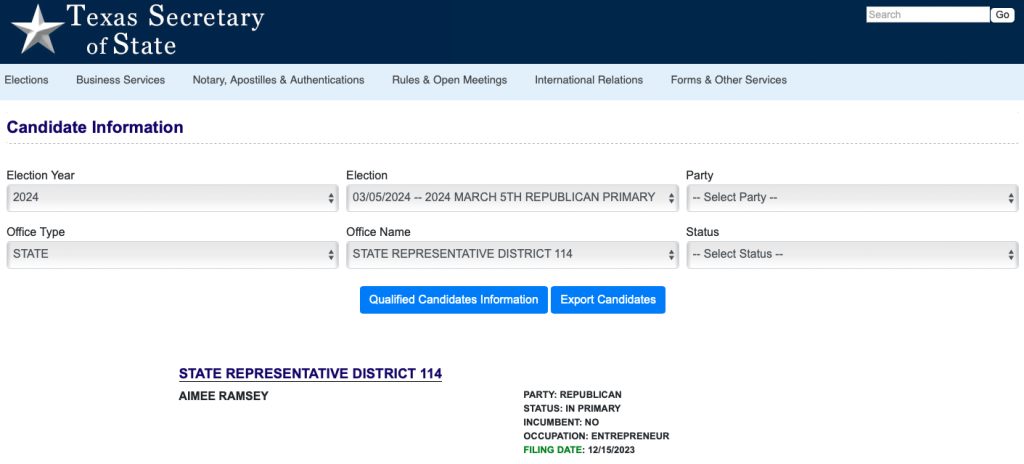

A Tale of Two Interpretations: Aimee Ramsey, District 14

Isom wasn’t alone. Aimee Ramsey, seeking a place on the ballot and the chance to represent District 14, also found the door slammed in her face. Both submitted their applications on February 7, according to their accounts. Later that day, Ramsey learned of her ineligibility, while Isom received his initial approval.

Seeking answers, Ramsey gathered all the submitted and approved applications, noticing a stark difference between her own and those of other hopefuls (besides Isom): she had checked the box acknowledging a prior felony conviction. This prompted a conversation with Isom, with Ramsey inquiring about any additional documentation Isom may have submitted. His answer: none. Confused by the inconsistencies, suspecting a bureaucratic blunder, she began making inquiries with the city secretary and her legal counsel, who initiated discussions with the city on her behalf.

Ramsey shared with the Nomad that her past conviction for “misprision of a felony”—legal jargon for the active concealment of a known felony—stemmed from a desperate choice she made in 1996 to protect her young child and unborn baby. “They threatened me, and I was at risk of losing them,” she recounted, the echo of that pressure still audible in her voice. She chose the guilty plea, taking responsibility for what she now calls “doing something dumb” as a young woman.

In 2024, despite her past, she ran for Texas State Representative – House District 114 in Dallas County and was approved by the Secretary of State. “I turned in the exact same application. All of my documentation was the same for the 2024 primary,” she explained. Her discharge documentation, she said, was accepted as proof of being “otherwise released from the resulting disabilities,” as stipulated in Texas Election Code § 141.001(a). She even won the primary and appeared on the November general election ballot.

Yet, with no change in the law or her status, Dallas City Hall slammed the door on her 2025 City Council bid. “How can someone be eligible for state office in Dallas but ineligible for local office in the same city?” the District 14 hopeful questioned.

The city’s response pointed to the Texas Election Code, a document seemingly open to interpretation. The Code, a broad stroke of instruction, stipulates that individuals with felony convictions may run for office if “otherwise released from the resulting disabilities.” The City of Dallas, however, leans on Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s Opinion KP-0251, a finer, more specific interpretation, arguing that only pardons, judicial clemency, or specific statutory restoration of rights qualified.

The city seemed to have adopted a blanket policy—if one formerly convicted individual was deemed ineligible, all others would be as well. She suspected her inquiries, perhaps poking a raw nerve of inconsistency, had inadvertently triggered the reconsideration of Isom’s case.

But whispers also circulated, carried on the same winds that rustled through City Hall’s aging oaks, of another catalyst. A reliable source at City Hall spoke of a hushed conversation where another name had been mentioned alongside the caveat of a felony conviction, access to the ballot, and the looming 2025 election.

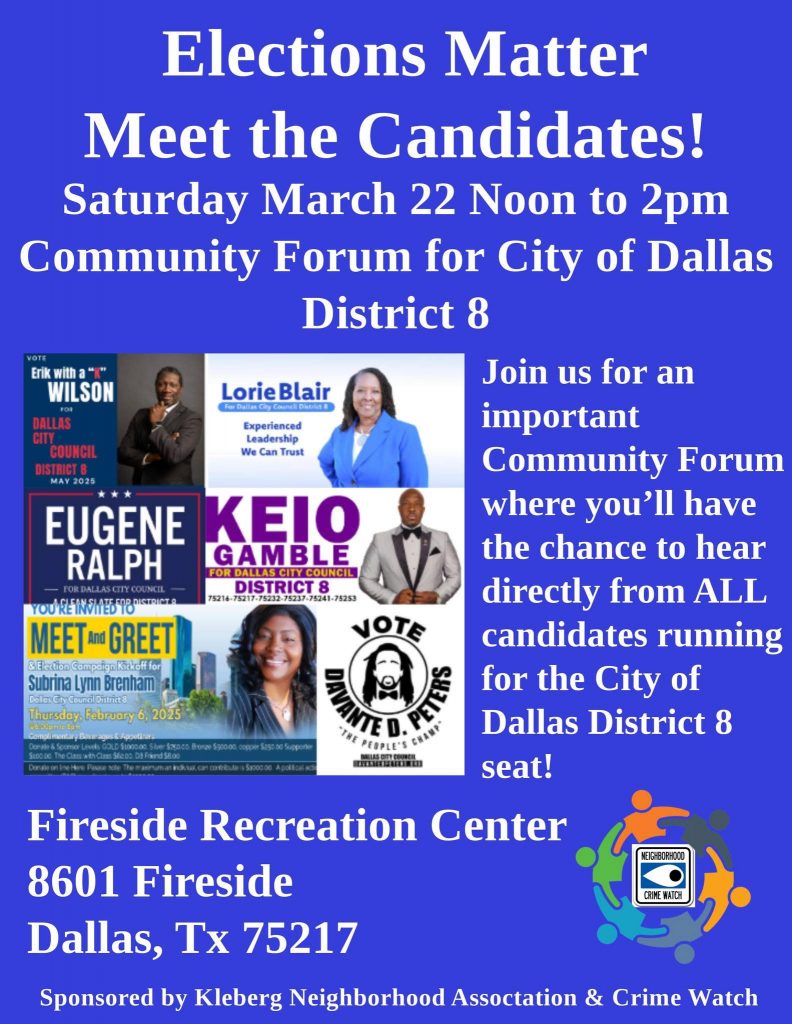

Potential Political Maneuvering: Keio Gamble, District 8

Keio Gamble, a candidate for District 8, submitted his application on February 14th, his eyes wide open to the obstacles already tripping up Isom and Ramsey. He knew, with a certainty that settled deep in his bones, that his own path wouldn’t be smooth. A formerly convicted felon, now a man dedicated to public service, Gamble told the Nomad that he had been “completely cleared in 2013 of a possession of marijuana charge that stemmed from 1998.” Always draped in a suit and tie—his self-described “uniform”—Gamble outwardly clung to that clearance like a lifeline, a testament to his transformation.

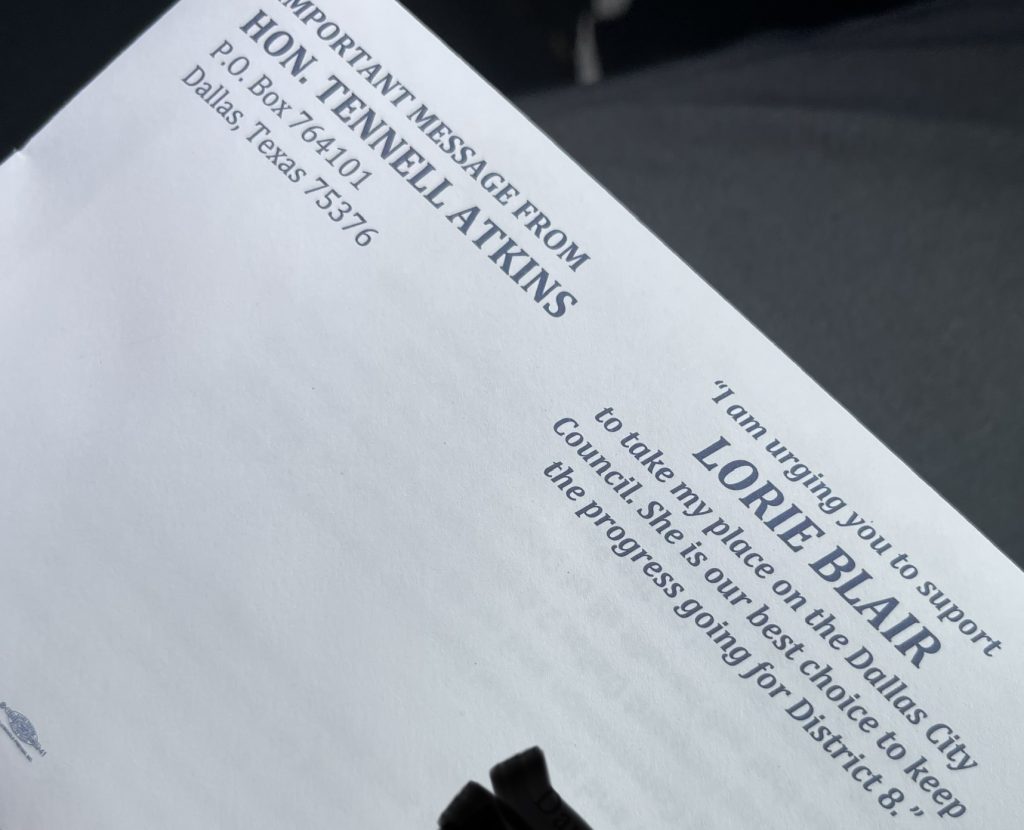

But some whispered a different narrative, one painted with the hues of political intrigue. An anonymous source in City Hall, reliably close to the city’s pulse, claimed that outgoing City Council member and Mayor Pro Tem Tennell Atkins had leaned on connections and favor at City Hall, allegedly questioning Gamble’s eligibility because of his past.

The catalyst? The source suggested it was a flyer. A simple flyer, advertising a “Meet the Candidates” event sponsored by the Kleberg Neighborhood Association and Crime Watch. Six of the seven District 8 hopefuls were included on the flyer, including Gamble, who planned to run with the slogan, “People over Politics.” That flyer, the source implied, had piqued Atkins’ attention, perhaps igniting a spark of concern at what they perceived as a challenge to his alleged chosen successor, Lorie Blair, for whom Atkins had already begun campaigning via mailers. The flyer, seemingly innocent, may have inadvertently cast his past not as a closed chapter, but as a weapon in the game of city politics.

Atkins’ and Blair’s mutual ties to developers, such as Russell Glen (Shops at RedBird) and LDG Development (The Ridge), would ensure continued support for development within District 8, which is currently at risk of gentrification.

The source says this led to a visit to City Hall, where Gamble’s past felony conviction was brought to the attention of city officials, potentially triggering the city’s sudden shift in policy regarding candidate eligibility. While unable to pinpoint the exact date, the source said the interaction took place on either February 7 or 10.

“I got my letter stating they couldn’t qualify me. I expected that,” Gamble tells the Nomad. He says that after a productive conversation with the city secretary about next steps, he fully expected to be approved for the ballot the following week, an expectation that was dashed when his petition was denied.

“They’re afraid,” Gamble said—”They know that I have a good chance of winning and that scares the powers that be.” This broader approach, whether intentional or a reaction to the council member’s alleged involvement, effectively disqualified multiple candidates, raising questions about whether the city’s actions were a legal interpretation or a politically motivated maneuver.

A Double Standard?

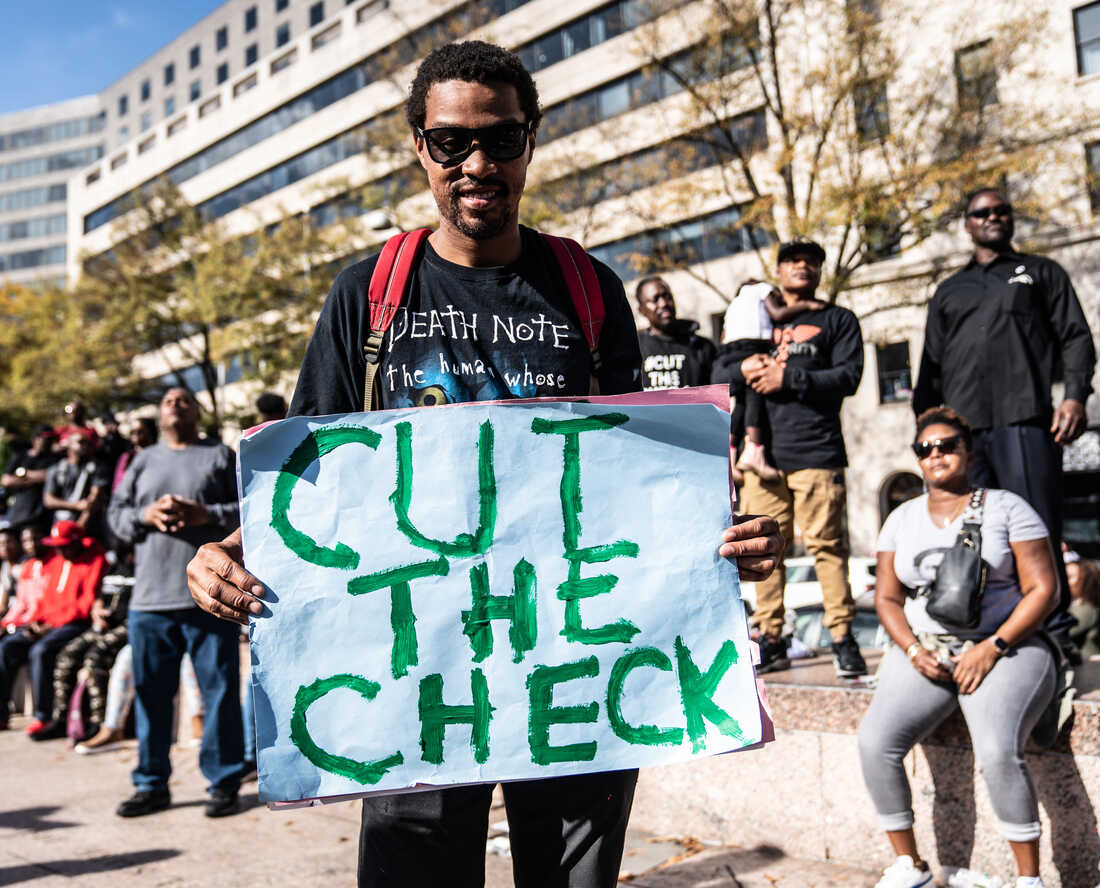

“They want us to keep paying for mistakes we made when we were young,” Ramsey said, her voice laced with frustration. “What we’re trying to do is the literal definition of reform. And then they get in these positions and commit crimes right in office.” It’s a common refrain among the candidates caught in this political tangle: a sense of perpetual punishment for past errors, even as they point to the less than spotless pasts of sitting officials. This frustration is compounded by the perception that second chances and opportunities for reform are selectively applied—reserved for some, denied to others.

Following the scandal in 2019 exposing bribery of former Dallas City Council Member Carolyn Davis by developer Ruel Hamilton, greater claims of corruption from within city government have dogged local politicians. This event coincided with similar cases of bribery involving developers Sherman Roberts and Devin Hall, who each funneled thousands of dollars in exchange for support of beneficial tax credits and fiduciary support of real estate endeavors.

Poor conduct was confirmed by Corbett Smith in an investigation published by Dallas Morning News, where it was revealed that the majority of city council members in Dallas have accepted donations far beyond limits while listing other questionable contributions from children. Of those noted, Atkins, Carolyn King Arnold, and Omar Narvaez are the remaining members still serving the council. And although these were chalked up as “errors” made in “good faith,” many have still called this for what it is: a “free-for-all” amidst lack of oversight. Mayor Pro Tem Atkins’ two predecessors have both been handed ethics violations as well, from the relatively mild scandal involving Casey Thomas’ violation involving VisitDallas to Dwaine Caraway’s explosive 2018 bribery case.

Likewise, Atkins has stoked controversy in several other scandals throughout his career in City Council. In 2014, Atkins was accused of assaulting Raquel Hultquist, a City Hall employee. Hultquist had refused him entry to the building because he lacked appropriate identification. In 2015, Atkins was found guilty, issued a misdemeanor Class C assault citation, and ordered to pay a $100 fine. Then, in 2021, a complaint alleged that Atkins improperly influenced city staff to destroy water-saving landscaping at the Singing Hills Recreation Center, violating city charter, ethics code, and procurement rules. Atkins reportedly disliked the look of the native grasses and demanded they be replaced with buffalo grass, resulting in $20,000 in damages and increased maintenance costs. City staff claim the decision wasn’t theirs, and one suggests Atkins’ concern was driven by “publicity.”

This apparent double standard has fueled a growing discontent within the Dallas political landscape. This discontent is timely, as Proposition E, which passed in November with nearly 70% of the vote, amended the city charter to establish term limits for the mayor and city council. The amendment bars the mayor from serving more than two four-year terms and council members from serving more than four two-year terms.

Dallas community leader and real estate developer Derek Avery, a 2024 candidate for Dallas County Commissioner District 3, believes this opens the door for newcomers previously shut out of city politics. Avery also believes that while a significant shift is underway, political maneuvering remains ingrained in Dallas’ political culture. “The establishment is slowly becoming obsolete,” Avery observed. ‘People are frustrated with the lack of tangible results, and they’ve become pissed off enough to act.’

Despite his own electoral setback, Avery remains a force in the community, particularly through his work in Sandbranch. He sees the growing number of candidates vying for office as a sign of positive change. “This is good,” he says, “to have competition outside of the typical consultants and old guard. The proverbial kissing of the ring is not the only way into leadership in Dallas anymore.” Avery welcomes this disruption, believing it will energize voters and lead to a government that truly reflects the people it serves. “The shift is welcomed,” he concluded, “and I’m personally excited to see voter turnout increase.”

On the City’s Stance and Legal Challenges

Despite these setbacks, all three candidates are standing firm. The excluded three argue that the city is misinterpreting the legal opinion KP-0251, contending that it focuses specifically on pardons, not the broader category of being “otherwise released.” The “or” in the election code, they emphasize, creates two distinct pathways to eligibility: being pardoned or being otherwise released. Gamble, in a scathing letter to city officials, pulls no punches. “The City Attorney’s office is just missing the ‘or’ in the sentence,” he wrote. “Or, maybe they are purposely ignoring it to secure personal gain through political favors.” Gamble’s letter also alleges that a current council member conspired with the City Attorney’s office to block his candidacy, while also citing a vested interest in a competing candidate.

The candidates also accuse the city of ignoring established precedent. They point to a string of similar cases across Texas. In 2018, Lewis Conway, Jr., made history as the first formerly incarcerated person in Texas to have his name on a ballot, running for office in Austin. In Killeen (Roslyn Finey, 2020/2021) and DeSoto (Everett Jackson, 2025), candidates with felony convictions, presenting similar discharge documentation, were deemed eligible. These cases, though not widely publicized, paint a picture of consistent practice: proof of sentence completion or termination of supervision is being accepted as evidence of being “otherwise released from the resulting disabilities,” fulfilling the requirements of the Texas Election Code.

Adding fuel to the fire is the 2020 ruling in Jefferson-Smith v. Bailey. This landmark case cleared the way for a candidate with a felony conviction, Cynthia Bailey, to appear on the ballot. The case consequently established a statewide precedent, explicitly stating that municipal authorities lack the fact-finding authority to disqualify candidates based on prior felony convictions when evidence of rights restoration—other than a specific list of documents related to pardons—is provided. The court’s decision underscores the limitations of local authorities in these matters, further weakening the city’s legal position.

So What Now?

“This isn’t just about individual candidacies; it’s about ensuring that everyone, regardless of their past, has a fair chance to participate in shaping the future of our city,” argues Gamble. Isom sums up the experience: “As to the reversal,” he stated, “well, if it’s not [overturned], and we’re kept off the ballot, then we openly question the ethical and moral practices of those in and around this who are supposed to be representing the well-being of the people.” He added, “The outcome of that determines a lot. But, the work we do must go on regardless.”

Ultimately, a court may have to decide which argument prevails, weighing the letter of the law against the established practice of its application. This decision will not only determine the fates of these individual candidacies but also set a precedent for future cases, shaping the landscape of ballot access in Dallas and potentially across Texas.