Echoes of Injustice: Immigrant Detention, Boarding Schools, Mass Incarceration, and the Construction of “Enemies”

From the Alien Enemies Act to the detention of Venezuelan immigrants, history reveals a disturbing pattern of creating 'enemies'

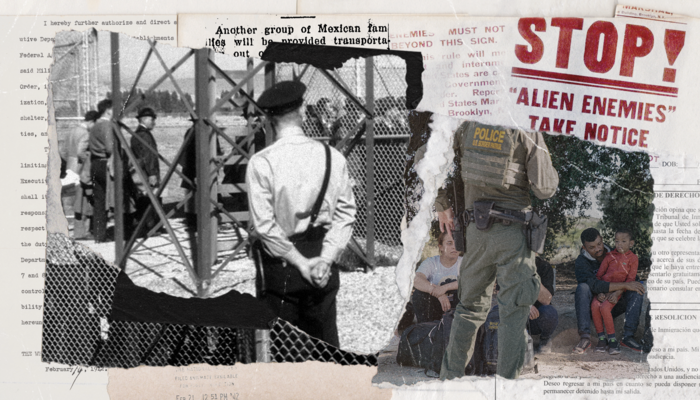

From the Alien Enemies Act to the detention of Venezuelan immigrants, history reveals a disturbing pattern of creating ‘enemies’ to justify oppression. Echoes of past injustices – Native American boarding schools, mass incarceration, and Japanese American internment – juxtaposed against mass deportations in today’s headlines are challenging the illusion that ‘it can’t happen here’.

Recent images of Venezuelan immigrants detained in overcrowded El Salvadoran prisons, facing deportation, have sparked a visceral reaction across the globe. Social media platforms have buzzed with outrage, commentary, and thought pieces, highlighting the stark conditions and raising questions about human rights.

Yet, amidst the digital outcry, there’s a palpable undercurrent of ‘oh well,’ a sense of detached observation. It’s a complex picture, where genuine concern mingles with the reality that political talk has increasingly become about creating viral content rather than fostering contextual thought. In an era where news cycles are driven by sensationalism and the potential for online virality, it’s easy to mistake amplified voices for widespread outrage. And perhaps, more concerningly, it seems many Americans, lulled by a false sense of security, believe such distant injustices could never touch them. This isn’t just a matter of indifference; it’s a reflection of our collective tendency to believe that what happens to ‘others’ is somehow fundamentally different from what could happen to ‘us.’

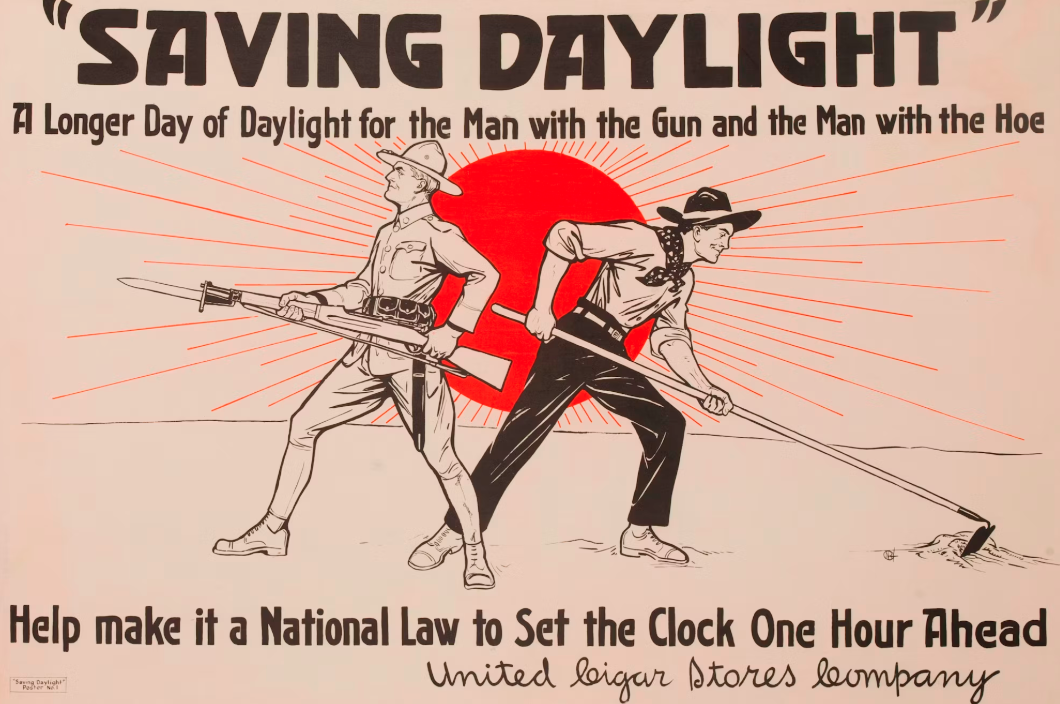

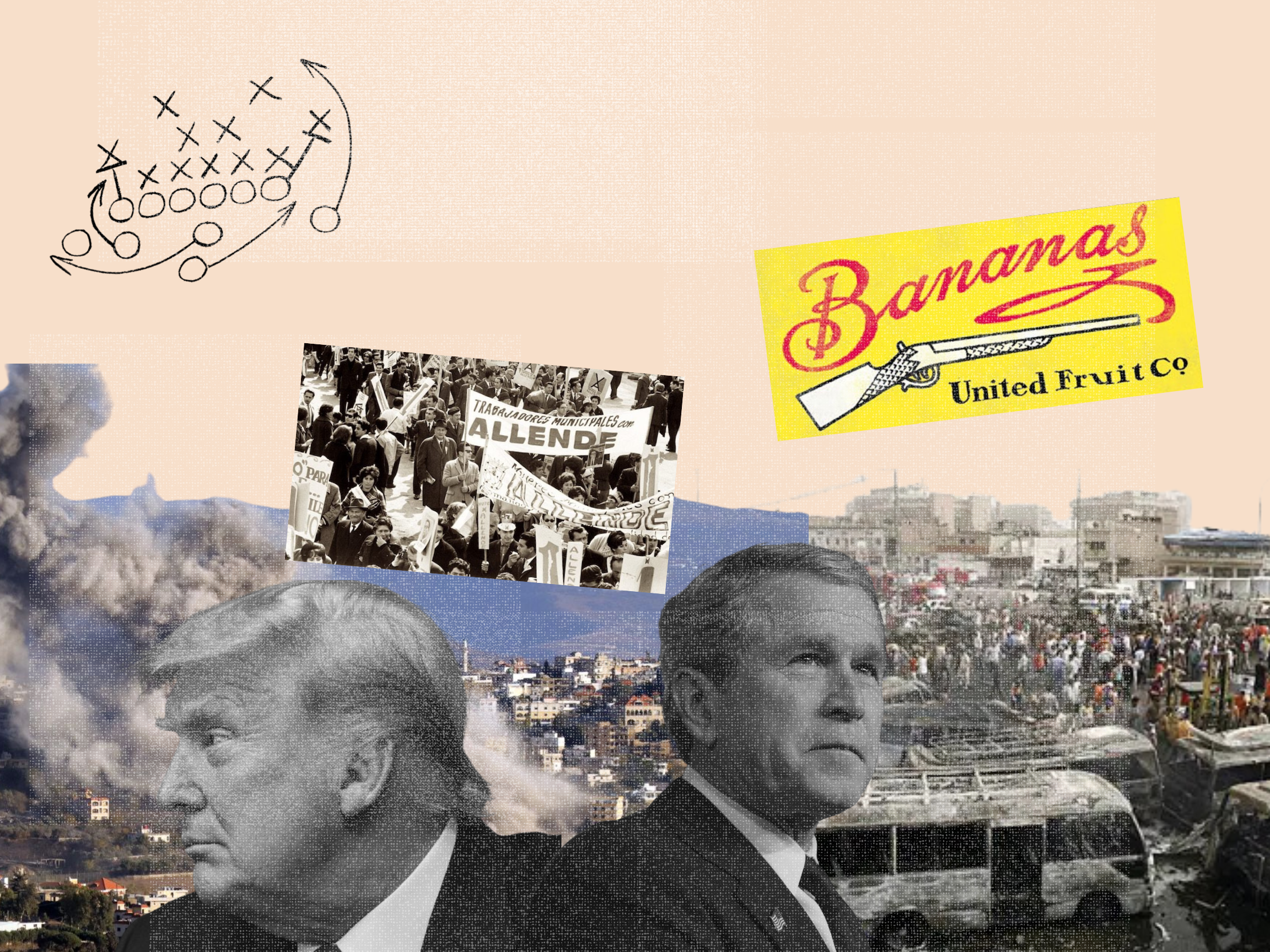

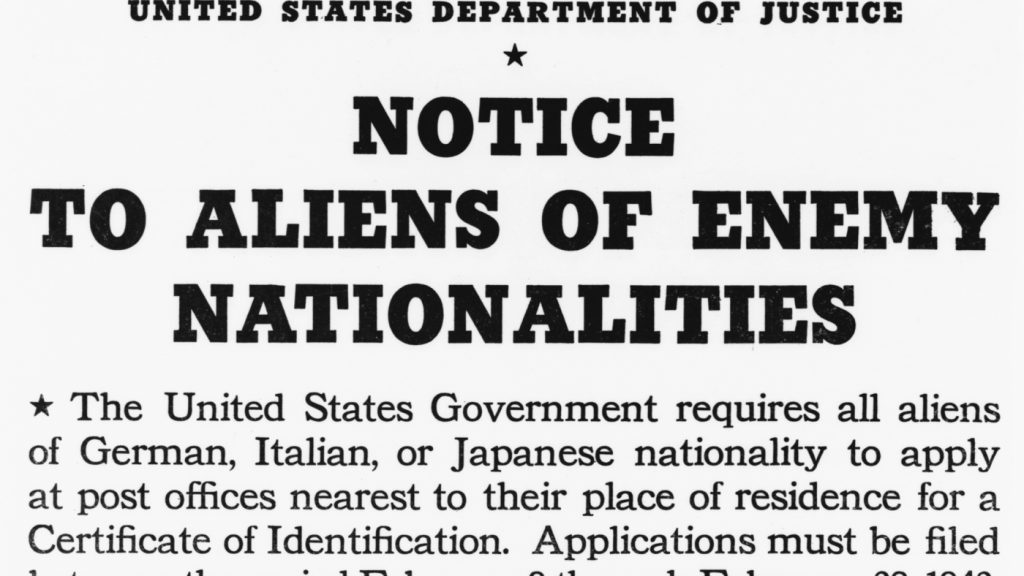

Adding a layer of complexity, justifications for the most recent wave of deportations and detentions have invoked the specter of national security, with President Trump using his increasingly consolidated executive power to leverage the 227-year-old wartime Alien Enemies Act, a law designed for, well, times of war, to legitimize the treatment of these ‘enemies.’ The last time a president invoked the Alien Enemies Act was during World War II, after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, when the United States declared war on Japan and Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S. The Act was used to detain people of Japanese, Italian and German ancestry.

Though today, there’s one major problem: the United States is not at war with Venezuela. Instead, these Venezuelan deportees were publicly labeled ‘enemies’ after being identified, according to official statements, as members of the gang Tren de Aragua, which was recently designated as a U.S. Foreign Terrorist Organization. Notably, evidence supporting claims that the deported individuals are Tren de Aragua gang members has not been made publicly available by the Trump Administration.

While the conditions in El Salvador are undeniably harsh, it’s crucial, now more than ever, to examine how the situation we’re watching unfold resonates with historical injustices within the United States, namely the forced assimilation of Native Americans in boarding schools, the mass incarceration of Black Americans, and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. These are not isolated events; they are threads in a tapestry of systemic enemy creation, and their echoes reverberate into the present, often in ways we fail to recognize.

The forced removal of Native American children to U.S. boarding schools during the late 19th and 20th centuries was a calculated act of cultural genocide, painting indigenous populations as ‘savages’ needing ‘civilization.’ This ‘enemy’ narrative justified the destruction of their culture and the forced separation of families. Children were forcibly taken from their homes, often by government agents or law enforcement, and transported to distant, often church-run, institutions. Once there, they were subjected to a litany of abuses: their traditional clothing was replaced with uniforms, their hair was forcibly cut, and they were forbidden to speak their native languages, facing harsh punishments for doing so. They were given new, Anglo-Saxon names, erasing their tribal identities. Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse were rampant, with children subjected to beatings, isolation, and other forms of cruelty. Disease spread rapidly in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, and many children died from illnesses like tuberculosis and measles. According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, thousands of Native American children died while attending these schools, and the trauma continues to impact generations, leaving deep scars of cultural loss, family disruption, and lingering psychological wounds.

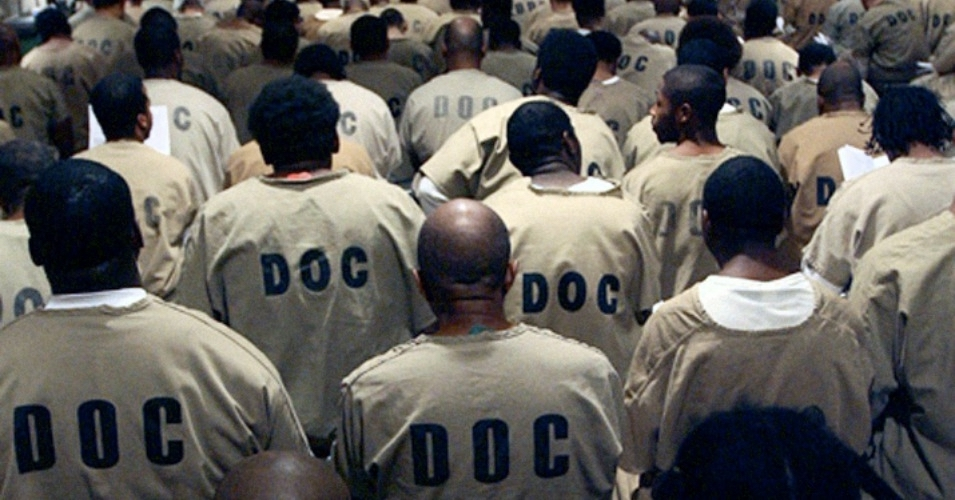

The mass incarceration of Black Americans, particularly in the post-Civil Rights era, provides another stark example. The legacy of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and racial segregation created a foundation for discriminatory practices within the criminal justice system. Here, the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,” was exploited to perpetuate a system of forced labor and social control. The War on Drugs, with its racially biased enforcement, and the passage of punitive crime legislation, including the 1994 crime bill, further solidified the perception of Black Americans as “criminals” and “enemies” of society, justifying disproportionate imprisonment. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Black Americans make up approximately 13% of the U.S. population but represent nearly 40% of the incarcerated population.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II also serves as a chilling reminder of how fear, prejudice and the creation of enemies can lead to the mass detention of an entire group of people. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes and businesses. Based solely on their ethnicity, they were placed in internment camps as the world watched the erosion of their civil liberties. Japanese Americans were painted, as an entire ethnic group, as potential “enemy agents.” Approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in internment camps.

It’s easy to believe that such a blatant violation of rights is a relic of the past. The perceived “comfortable distance” and the belief that ‘it can’t happen to me,’ is precisely the illusion that allows these cycles of injustice to persist. As Sinclair Lewis warned in his prescient novel, “It Can’t Happen Here,” the erosion of civil liberties and the rise of authoritarianism can happen anywhere, even in seemingly stable democracies, when fear and prejudice are exploited. This contentment often manifests as social media advocacy – retweets, shares, and online commentary – creating a sense of action without requiring actual engagement. It’s a digital echo chamber of outrage, but rarely translates into tangible change or people taking to the streets.

Many people find a sense of comfort in the belief that these injustices are distant, confined to history books and far-off lands. They reassure themselves that such atrocities could never touch their lives. However, this illusion of distance is a dangerous fallacy. For many Americans, the legacies of these historical injustices are closer and more deeply personal than they realize. Native Americans still carry the scars of forced assimilation, Black Americans still grapple with the ongoing effects of systemic racism, and Japanese Americans still bear witness to the violation of their civil rights. And for many people, their ancestors, grandparents, and parents were personally impacted by the actual history that still reverberates through our modern day-to-day lives.

Even those whose ancestors were not directly targeted by these injustices benefit from the systems of power that were built upon them. The economic and social advantages that some enjoy are often rooted in the exploitation and oppression of others. This is not about individual guilt, but about recognizing the systemic nature of these benefits. Consider, for instance, the legacy of land ownership: vast tracts of land, originally belonging to indigenous populations, were seized and redistributed to settlers, forming the basis of wealth for many families. The labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants built the foundations of industries and fortunes that continue to generate wealth today.

The portrayal of Mexicans as criminals, particularly along the U.S.-Mexico border, has been used to justify discriminatory policies and practices, echoing the construction of ‘enemies’ seen in other historical contexts.The detention of Venezuelan immigrants in El Salvador, while occurring outside U.S. borders, reflects similar patterns of injustice, raising questions about human rights and the treatment of vulnerable populations that are easy targets to be made “enemies”.

And there lies a crucial point: the construction of ‘enemies’ is not merely a byproduct of fear and prejudice; it’s a tool of power. Those in positions of authority often find it beneficial to rally the country around a common threat, real or perceived. It consolidates power, diverts attention from internal problems, and justifies actions that would otherwise be deemed unacceptable. This manipulation of fear is a recurring theme throughout history, and it’s essential to recognize its insidious nature.

Therefore, I call on you, the reader, to look for the patterns. Examine the historical echoes in current events. Question the narratives that paint certain groups as ‘enemies.’ And most importantly, think critically about what actual resistance looks like. It’s not just about online outrage or fleeting moments of solidarity. It’s about sustained engagement, informed action, and a willingness to challenge the systems that perpetuate injustice. Remember, these patterns are not confined to history books or distant lands. They are happening right here, right now. And it is up to us to recognize them, and to resist them.