Studies, Schmudies: Wes Moore and the Audacity of Action

Forget the footnotes, Governor Wes Moore is ditching the endless reparations studies and hinting it's time to actually, you

Ah, the noble study. The hallowed document, filled with charts, graphs, and the kind of jargon that makes even seasoned policy junkies reach for a stiff drink. For decades, it’s been the go-to move for politicians facing touchy issues, a way to kick the conversational can down the road, keeping the discussion going while, in the grand scheme of all of the policy things always happening all at once, accomplishing very little save, well, more discussion. And when it comes to the long, painful history of reparations for Black Americans, the study has reigned supreme, a perpetual holding pattern in the face of centuries of injustice.

We’ve studied, sure. But we’ve talked about it, too – a lot. So much so that one of the generation’s greatest minds, Ta-Nehisi Coates, laid out one of the most recent and, arguably, one of the most powerful cases in his influential 2014 Atlantic article, aptly titled “The Case for Reparations.” Coates even testified before Congress, further underscoring the urgency and moral imperative.

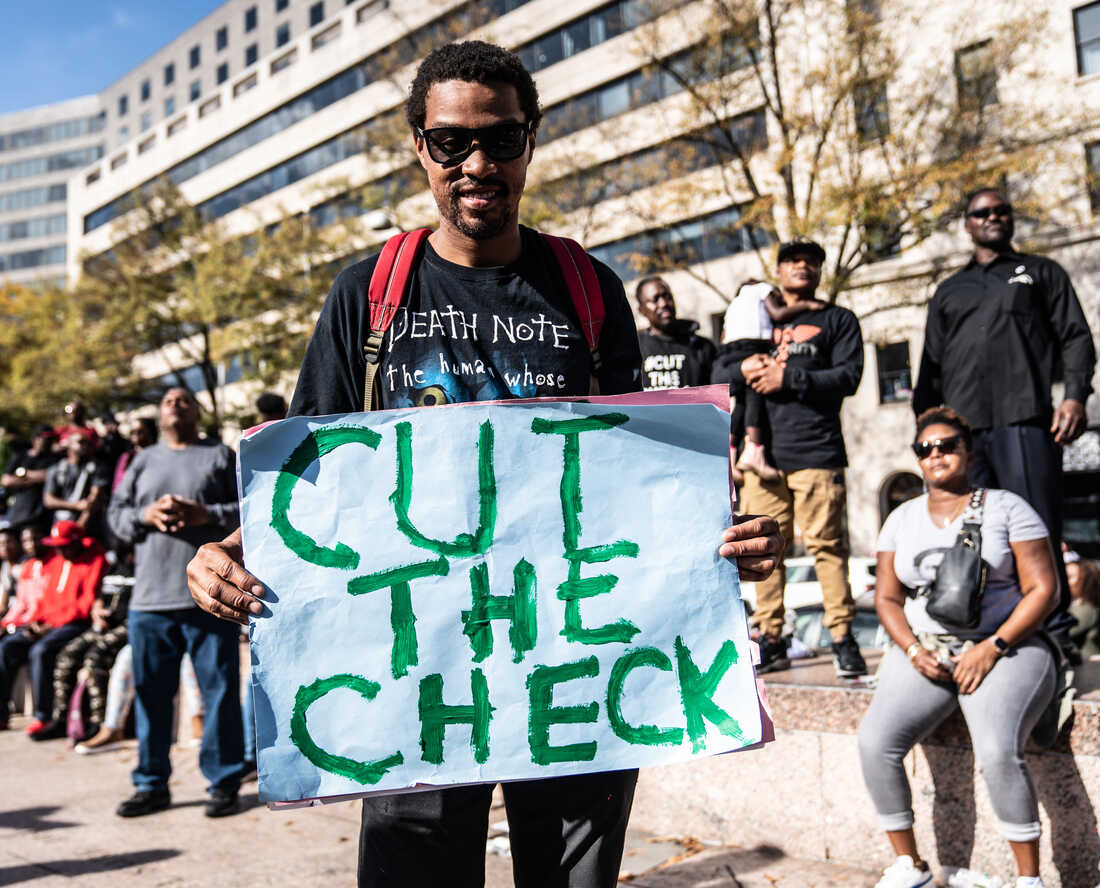

Still, the ongoing debate around reparations can sometimes feel like that perpetually planned group trip. We’ve got endless hotel options debated in the group text, travel dates, a color-coded itinerary of prescribed activities, and impassioned promises of ‘this time it’s really happening!’ Yet, somehow, no flights are booked, no hotels are confirmed, and the whole endeavor remains stubbornly confined to the digital realm of ‘just plans.’ In the case of reparations, we’ve thought, we’ve studied and we’ve talked. We’ve yet to actually act.

But! Enter Maryland Governor Wes Moore, a man who, it seems, has decided he’s had quite enough of academic navel-gazing. He recently vetoed a reparations study bill, and in doing so, he might have just committed the ultimate political faux pas: he actually wants to do something. Not just talk, not just theorize, but act.

As for me and my house? Moore’s veto letter was a breath of fresh air, a rare moment of clarity in the often-murky world of policy. He didn’t deny the need for reparations; in fact, he affirmed it. What he did deny was the need for yet another study, pointing to the state’s already existing commissions on lynching and the legacy of slavery. “Now is the time for continued action that delivers results,” he declared, and one can almost hear the collective gasp of the study-loving crowd, their meticulously crafted spreadsheets suddenly rendered obsolete.

Now, let’s be clear: around here, we believe in science! We do academics. So we know that studies have their place. They can provide valuable data, illuminate the nuances of complex issues, and guide policy decisions. We need only look at the meticulous, long-term planning executed by advocacy groups and far-right think tanks that, brick by brick, election by election, strategically laid the groundwork for the authoritarian regime we’ve found ourselves under, to understand the power of well-executed research and strategic thinking. The difference though is that all of that thinking and studying and planning was then combined with strategic, and at times incredibly bold, action in order to yield results. But a glaring complaint from the Democratic Party’s base has been the party’s perceived disconnection and consequential ineffectiveness, the sense that while they think, they rarely do.

“Now is the time for continued action that delivers results”

-Maryland Governor Wes Moore

When it comes to the glaring, undeniable reality of the racial wealth gap, the disparities in homeownership, and the systemic inequalities that continue to plague Black communities, how many more studies do we really need? We’ve got enough data to wallpaper the Library of Congress, data that has been meticulously compiled and passionately argued, as Coates so eloquently did nearly a decade ago.

At this point, it’s like commissioning a study on whether gravity exists. We already know it does; those of us over 30 are reminded of the 9.8 m/s2 of force pushing down on us every time we try to drop it low, and then spend the next three business days trying to get back up.

What Moore seemed to demand was solutions, not more data points. He’s calling for action, for tangible results, for policies that actually uplift Black families and address racial disparities. He’s suggesting that maybe, just maybe, the time for endless deliberation is over, and the time for actual, meaningful change is here.

Of course, this isn’t to say that the path forward is easy. Reparations, though a moral imperative, have been deliberately cast as a complex issue, fraught with historical baggage and political minefields, perhaps conveniently forgetting that Black Americans have stood watch while other harmed groups received compensation for their pain and suffering. The U.S. government, for instance, provided reparations to Japanese Americans who were unjustly interned during World War II, and even to some Native American tribes for the seizure of their lands.

One might even suspect the true complexity lies not just in the moral argument, but in the sheer size of the check the U.S. would have to write – with estimates ranging from hundreds of billions to potentially over $12 trillion to truly close the racial wealth gap, and California’s proposed program alone exceeding $800 billion. Yet, Moore’s stance is a refreshing reminder that sometimes, the best way to tackle a problem is to, well, actually start tackling it, even if it means wading into the political swamp.

And let’s not ignore the elephant in the room: 2028. Wes Moore, with his charisma, his compelling personal story, and his undeniable political savvy, is widely seen as a rising star in the Democratic Party. This veto, with its bold stance and its clear message of action, could be a calculated move to position himself as a leader who isn’t afraid to take on tough issues and demand meaningful policy. Which is, again, refreshing.

Though there was a very real risk that the veto-happy Moore, like predecessors such as Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, would be perceived by Black Americans as yet another politician who talks a good game, but refuses to deliver tangible results. However, Moore’s veto was not an isolated incident. He also vetoed a handful of additional bills that would have funded studies on climate change impacts, data center analysis, and youth technology resources, citing the state’s current budget constraints.

Notably, the Maryland Governor issued a dedicated letter to explain his veto of the reparations bill (SB 587), applauding the legislature’s work and giving a nod to the Black Caucus. This contrasted with his combined veto commentary on the other study-related bills (SB 149, HB 128, SB 116, HB 270, and HB 1316), where he emphasized that “while such bills can be a first step to addressing complex issues,” the “current budget situation requires us to reconsider bills that create expensive and labor-intensive studies.” This nuanced approach suggests a strategic awareness of the political landscape, both within and beyond the Black community. Moore seems to be sending a signal that says he’s prioritizing tangible outcomes over further deliberation. Yet, one can’t help but wish he would have used this moment to issue a clear call to action to the legislature for policy that takes the fight for reparations out of the study stage and into the realm of strategic, targeted implementation.

Some might call his move bold, even reckless. Others might call it common sense, or perhaps even a savvy political play. After all, the consensus is clear: Black American descendants of enslaved Africans are owed reparations. The question is not if, but how. And while the study-loving crowd is busy debating the finer points of methodology – meticulously comparing hotel reviews for that trip that has yet to leave the group chat – Moore seems busy trying to bridge the gap between the endless planning and actual departure, perhaps one that leads to a certain address in Washington D.C.

Maybe, just maybe, Governor Wes Moore is onto something. Maybe, just maybe, it’s time for other policymakers to follow his lead, to trade in their spreadsheets for shovels and start building. Because while studies might make for good reading material, they don’t build homes, close wealth gaps, or feed hungry children. And in the end, isn’t that what really matters? And might, just might, be the kind of message that resonates in a presidential election? Only time, and a few more bold moves, will tell.